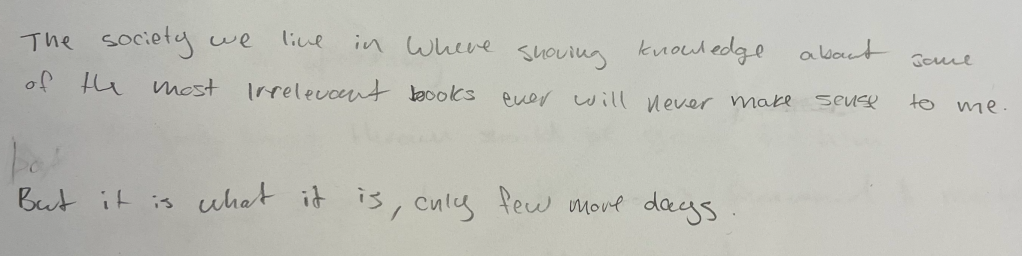

*Pictured above reads: “The society we live in where shoving knowledge about some of the most irrelevant books ever will never make sense to me. But it is what it is, only few more days.” The student wrote this to me in their Macbeth unit test.

First and foremost, I have no problem with this student voicing their opinion. It is their right. It is how they feel. In fact, it is likely how many students feel and it just so happens that they had to guts to let me know.

In the note, I see one main concern: They want to know the relevance of the material being taught.

It’s the same old story, really. Ask any math teacher if they’ve ever heard the question: “When will I ever need this?”

On day one of a fresh semester, I make sure students understand that my goal is not to make them LOVE literature, but rather to understand it. I don’t try to burden myself with the belief that my students will suddenly want to run to the local bookstore and grab a classic or the newest bestseller. In fact, I make it quite simple: I will equip my students with reading strategies so they can read a text and understand it. If I am also so lucky, I can get the students to a place of self-reflection.

Reading is challenging. If a student sees literature as a bunch of characters and stories that have nothing to do with them because the characters are “not real”, then yes, one will fail to understand what literature can teach them. One of the first concepts I teach is the S.T.E.A.L chart – it is an acronym that helps readers connect with a character by analyzing: Speech, Thoughts, Effects on Others, Actions, and Looks. As a practice, I have students complete one on themselves – I have them write down a list of things they’ve said, thoughts they’ve had, the impact they’ve often had on others, things they’ve done, and the way they present themselves. Then, I have them imagine that someone were to find that list… What would they say about that person? What conclusions would they draw? Are they a positive person or a negative person? It’s only a snapshot of a person, but are there any fair judgements that can be made? What assessments can be made about the quality of that person’s character? And so on. This is the same thing we, as readers, try to achieve with the characters within a text. But if we create barriers between ourselves (as the reader) and the text, then there is only a small chance that the literature will have any meaning.

Anyway, back to the original complaint…

What can or should Macbeth teach us? Macbeth warns readers what can happen when greed consumes us and ultimately negatively impacts our decision-making and relationships. Macbeth’s ‘tragic flaw’ was overconfidence (according to the witches it is humanity’s greatest flaw) – so, what else can act as our own tragic flaw? How does the play teach us about gender stereotypes? What can it teach us about our own ambitions? The list goes on… Again, if the response to the play is, “Well, I’ll never be King so this doesn’t pertain to me” then that student is right, the literature just won’t make sense.

I told the student that we also live in a society where many students are quick to give up and often choose to solely participate in things that are for entertainment. Can Macbeth or 1984 or Lord of the Flies or Salinger’s work or any other great work of literature compete with TikTok and other forms of social media? That’s a tough sell. It’s like trying to make literature more appealing than drugs, alcohol, or pornography. I doubt many students are going to the classics for their next dopamine hit.

I told the student that I worry about a society that lacks grit, perseverance, and a desire to challenge oneself.

But, I continue on. I’ll take a lesson from Atticus Finch (To Kill A Mockingbird) and keep fighting the good fight against all odds simply because it is the right thing to do.

The student is right though… it is what it is.